3 Futures Map

Referring back to Section 1.4.2, the author noted that “By engaging with deep uncertainty, planners take on the challenge of building multiple worldviews as possible explanations of system behavior and change during conflict” (2018). While Croft does not delve further into how to develop multiple worldviews, there is a technique that is useful to develop and analyze future states. That technique is called Field Anomaly Relaxation and is the focus of this chapter.

3.1 Motivating Problem

How to develop and implement the the technique of Field Anomaly Relaxation to develop a futures map.

3.2 What We Will Learn

What Field Anomaly Relaxation Is.

How to Develop a Futures Map Using Field Anomaly Relaxation.

3.3 What is Field Anomaly Relaxation?

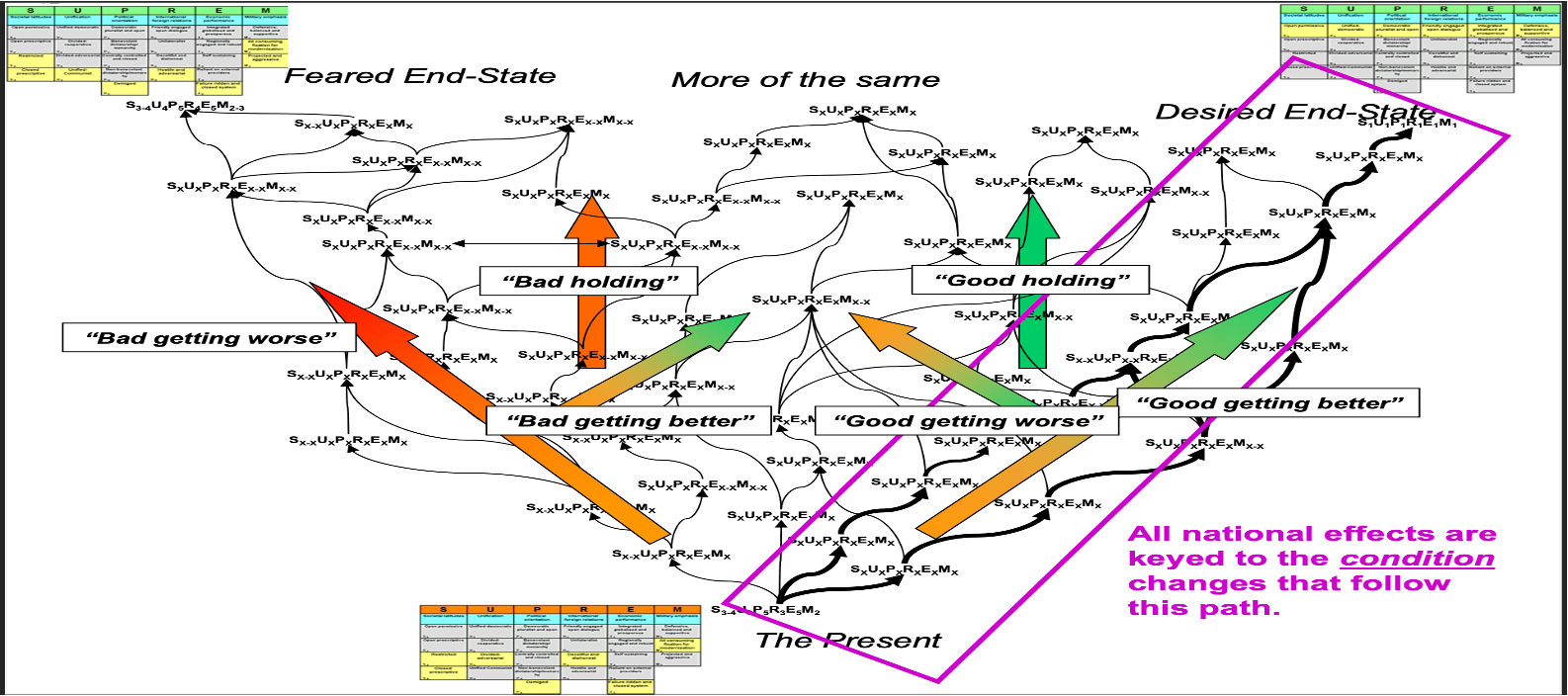

Field Anomaly Relaxation (FAR) is a scenario development methodology introduced by Russell Rhyne in the 1970s to support complex strategic and policy planning under deep uncertainty (R. F. Rhyne 1971; R. Rhyne 1995). FAR was designed not to predict specific outcomes, but rather to systematically generate and refine plausible descriptions of alternative future environments. These environments, or “contexts,” allow decision-makers to understand the conditions in which future decisions might be made. Rhyne argued that good decision-making depends not on a single forecast but on recognizing a range of coherent futures.

FAR accomplishes this through a structured and iterative process that filters out incoherent or internally inconsistent combinations of possible future conditions, leaving behind only scenarios that are logically plausible. These combinations are referred to as configurations and represent snapshots of what the world might look like across multiple dimensions or “sectors” (e.g., politics, technology, economics, culture).

The method emphasizes pattern recognition, participatory logic, and the elimination of contradictions, rather than numerical modeling or statistical forecasting. It encourages participants to articulate and refine their intuitive understanding of systemic change while ensuring logical consistency across variables. This makes FAR particularly well-suited for use in strategic foresight, defense planning, and long-range policy design (R. Rhyne 1995).

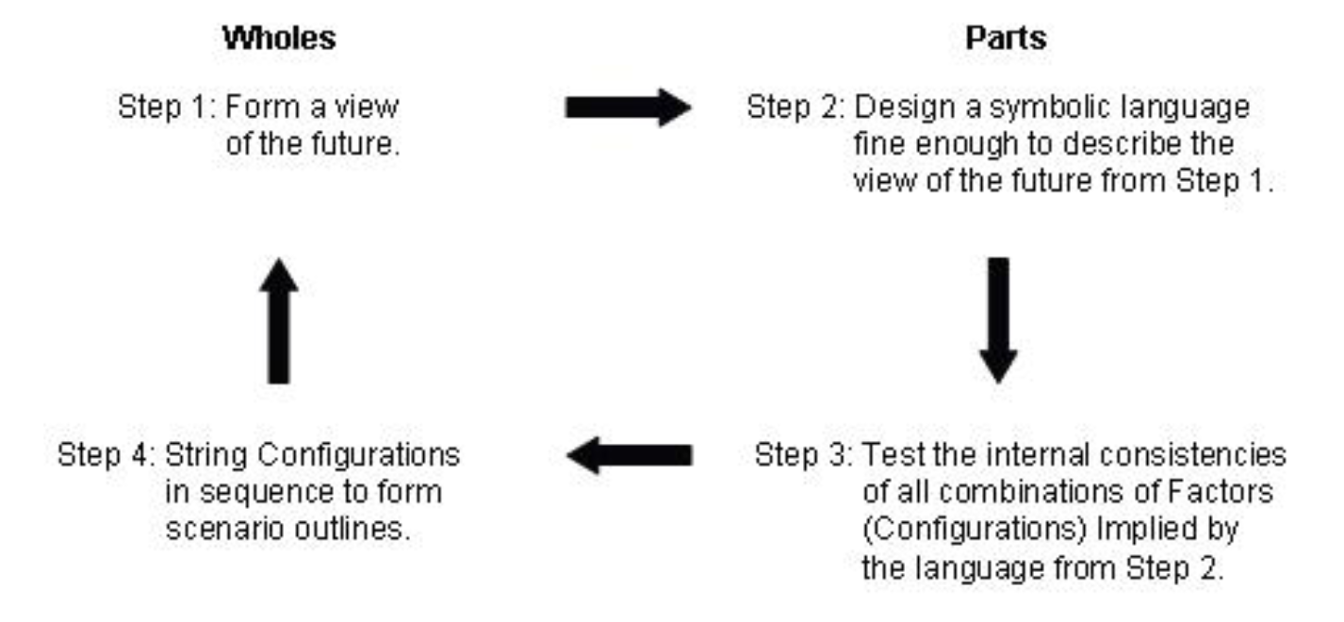

The FAR methodology proceeds in four steps: (1) forming a view of future contexts, (2) constructing a symbolic language, (3) filtering incoherent configurations, and (4) composing coherent scenarios.

3.4 Futures Map Development Steps

3.4.1 Step 1: Form a View of the Future

The first step in FAR involves developing a broad and imaginative view of what the future might look like in a given field or domain (R. F. Rhyne 1971). This is an exploratory process that calls on participants to articulate their implicit and explicit expectations about how key trends might unfold. Rather than starting with numerical forecasts, FAR encourages planners to begin with rough mental models or high-level narratives of plausible futures. The aim is to stimulate insight and creativity in thinking about possible worlds.

Participants identify “fields” of interest—broad systems such as national security or urban development—and sketch alternative configurations that might represent future states of that field. Importantly, participants are encouraged to think structurally rather than temporally, focusing on how elements of the system relate rather than on predicting timelines.

This step also helps uncover deeply held assumptions and prepares participants to build a formal language to describe configurations precisely. By beginning with open-ended exploration, FAR ensures that scenario building remains grounded while maintaining the flexibility to evolve.

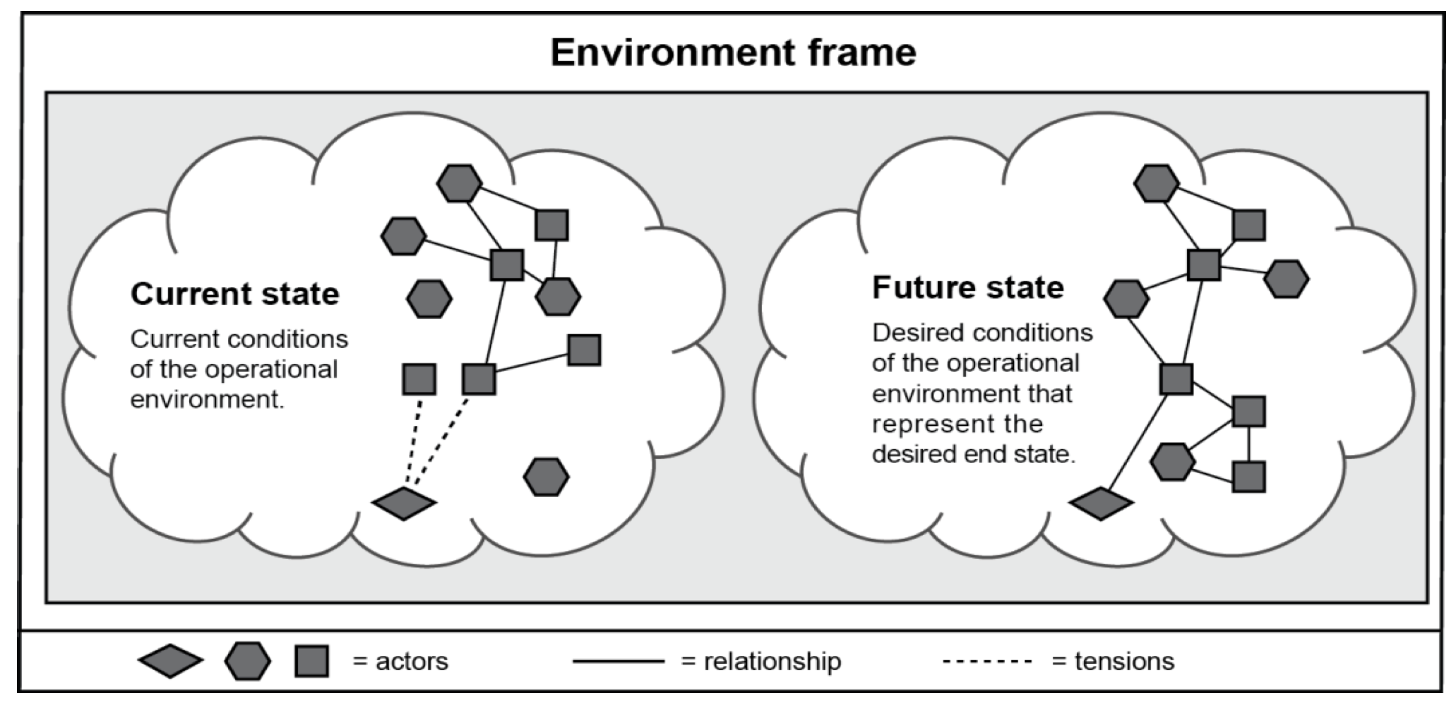

Step 1 of the FAR process closely aligns with the Army Design Methodology (ADM), particularly the step of framing the operational environment as shown in Figure 3.2. In this step, planners identify relevant systems, actors, relationships, and dynamics that characterize the current context. ADM emphasizes understanding complexity and interdependence across political, military, economic, social, informational, and infrastructure domains.

Both methodologies aim to uncover the fundamental structure of a complex problem before proposing solutions. FAR achieves this by identifying and categorizing dimensions that drive system behavior, while ADM does so through collaborative analysis and visualization tools like system maps and operational narratives. In both cases, the outcome is a more structured understanding of the problem that informs future exploration—whether through scenario generation in FAR or problem framing in ADM. Thus, FAR’s Step 1 complements ADM by offering a rigorous and disciplined technique for dimension identification, particularly when exploring alternative futures or dealing with deep uncertainty.

3.4.2 Step 2: Define a Symbolic Language

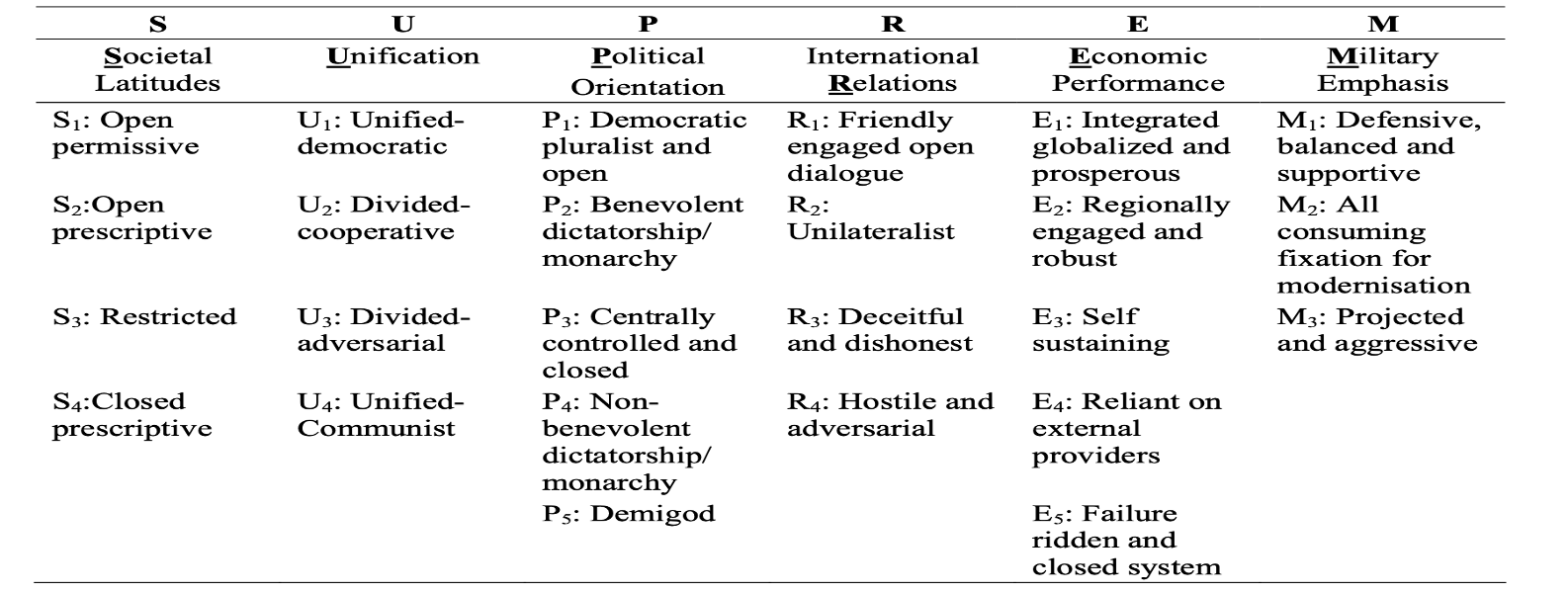

Once participants articulate initial visions of the future, they construct a symbolic language that adds structure and precision to those visions. This language consists of two key elements: sectors (broad categories like governance, technology) and factors (specific states within those sectors) (R. Rhyne 1995). Each configuration of the future is expressed as a combination of sector-factor pairs.

For example, a technology sector might have factors such as “high automation,” “AI dominance,” or “manual labor resurgence.” A governance sector might include “centralized control” or “decentralized autonomy.” This symbolic matrix enables planners to encode possible futures and identify logical dependencies among variables.

This structure allows participants to explore how combinations of factors interact across domains and whether they cohere into viable worlds. By creating a shared grammar, the symbolic language enhances communication, logic tracking, and transparency in scenario development (R. F. Rhyne 1971).

3.4.3 Step 3: Test Internal Consistencies

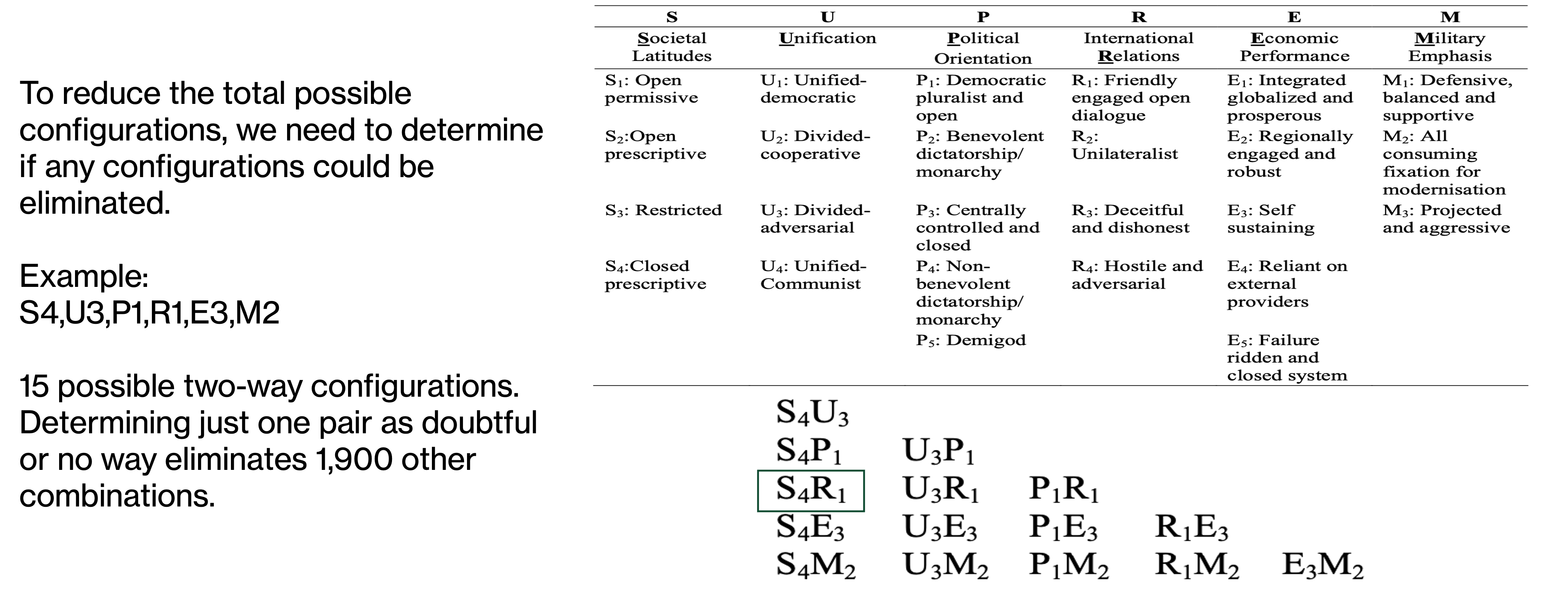

The most distinctive step in FAR is the systematic filtering of logically inconsistent or implausible configurations. Filtering occurs in two stages: pairwise factor analysis and whole-pattern coherence checking (R. Rhyne 1995).

In pairwise analysis, participants assess whether two factors from different sectors can logically coexist. For example, can “anarchic governance” coexist with “highly regulated markets”? If not, that pair is excluded from all further configurations.

Whole-pattern coherence checking then evaluates entire configurations for logical consistency and intuitive plausibility. This step relies on expert judgment and group deliberation rather than mathematical models. The process reduces a vast set of combinations to a manageable number of internally consistent, strategic futures suitable for planning.

3.4.4 Step 4: Compose Coherent Scenarios

In the final step, participants translate filtered configurations into rich, detailed scenarios. Each scenario describes a coherent future world, including causal explanations, key developments, and implications for strategy (R. Rhyne 1995). These narratives incorporate multiple dimensions (e.g., economic, political, environmental) and may use timelines or dramatizations to improve understanding.

Unlike predictive forecasts, these scenarios remain exploratory and policy-neutral, intended to serve as decision contexts. They help decision-makers explore “what-if” questions, anticipate disruptions, and design resilient strategies. The inclusion of time horizons and thematic grouping further supports actionable insight.

Through this process, FAR produces a small number of deeply coherent futures that organizations can use in wargaming, foresight analysis, or long-term planning.

3.5 Practical Exercise: Building a Futures Map Using Field Anomaly Relaxation

Scenario: Imagine you are a strategic planning team at U.S. Africa Command (USAFRICOM) tasked with exploring future environments for military engagement across the African continent in the year 2040. Your mission is to anticipate plausible strategic contexts that could affect campaign design, posture planning, and security cooperation.

You will apply the Field Anomaly Relaxation (FAR) method—referred to here as Futures Mapping—to build a set of internally consistent futures that support strategic foresight.

⸻

Instructions:

Form a View of the Future

Identify four sectors relevant to AFRICOM’s future operating environment (e.g., governance, technological diffusion, security cooperation, socio-economic development).

For each sector, brainstorm three plausible future states (factors).

Example: Sector: Governance | Factors: “Stable democratic institutions”, “Hybrid regimes”, “Autocratic resurgence”.

Define a Symbolic Language

Create a matrix of your four sectors and their respective factors.

Assign shorthand symbols to each factor (e.g., G1 = Stable Democracy, T3 = AI Dominance).

Test for Internal Consistency

Conduct pairwise analysis to identify any incompatible factor pairs.

Eliminate inconsistent combinations and record your rationale.

Compose Coherent Scenarios

From the remaining valid configurations, select two combinations to develop into rich narrative scenarios.

Describe the characteristics of each world, key events that led to it, and its strategic implications for AFRICOM.

⸻

Deliverable: Submit a table of sectors/factors, a visual diagram of your futures map (optional), and two ~200-word narrative scenarios that reflect coherent, plausible futures.

Objective: Apply structured logic to generate future scenarios that support adaptive planning and assessment under deep uncertainty.