5 Strategic Military Effects

A final theoretical piece of the military assessment puzzle focuses on strategic military effects. Analyzing military effects is a crucial topic that encompasses not only the debate over what constitutes an effect but also the key difference in how a military effect necessitates a distinct mode of thought, varying by the level of war.

5.1 Motivating Problem

How to think about and analyze strategic military effects.

5.2 What We Will Learn

What are military effects?

How strategic military effects are different.

A comparison of reductionist and systems thinking.

5.3 What are Military Effects?

According to JP 3-0 (2022), military effects are:

The physical or behavioral state of a system that results from an action, a set of actions, or another effect.

The result, outcome, or consequence of an action.

A change to a condition, behavior, or degree of freedom.

These effects can be direct, such as the destruction of an enemy capability, or indirect, such as influencing the will of a population. Effects can also be intended or unintended and may vary in scale, duration, and significance. Understanding military effects is critical for linking tactical actions to higher operational or strategic goals. At their core, effects represent a change in condition, behavior, or degree of freedom for an actor or system. This definition encompasses kinetic actions, like strikes, and non-kinetic actions, such as information operations or deterrent posturing. The comprehensive view ensures that planners consider both tangible and intangible results, enabling more effective integration of military activities with diplomatic, informational, and economic instruments of power in joint and combined operations.

5.4 What are Strategic Military Effects and Why are They Different?

Strategic military effects are the broad, enduring outcomes that connect military actions to national or alliance-level objectives. They often span across domains, geographic regions, and timeframes, involving complex, multi-factor relationships beyond simple linear cause-and-effect. Unlike operational or tactical effects, strategic effects require consideration of political, economic, social, and informational dynamics alongside military factors. For example, a military show of force may have the immediate effect of deterring adversary aggression, but its strategic effect could include strengthening regional alliances or altering global perceptions of resolve. Because these effects operate within a highly interconnected environment, they are influenced by feedback loops, cultural factors, and adaptive adversary behavior. Understanding strategic effects requires analysts to look beyond battlefield outcomes and assess how actions contribute to—or detract from—long-term strategic objectives. This broader perspective ensures that military planning supports national policy and accounts for second- and third-order consequences.

5.5 Reductionist vs. Systems Thinking

5.5.1 Reductionist Thinking

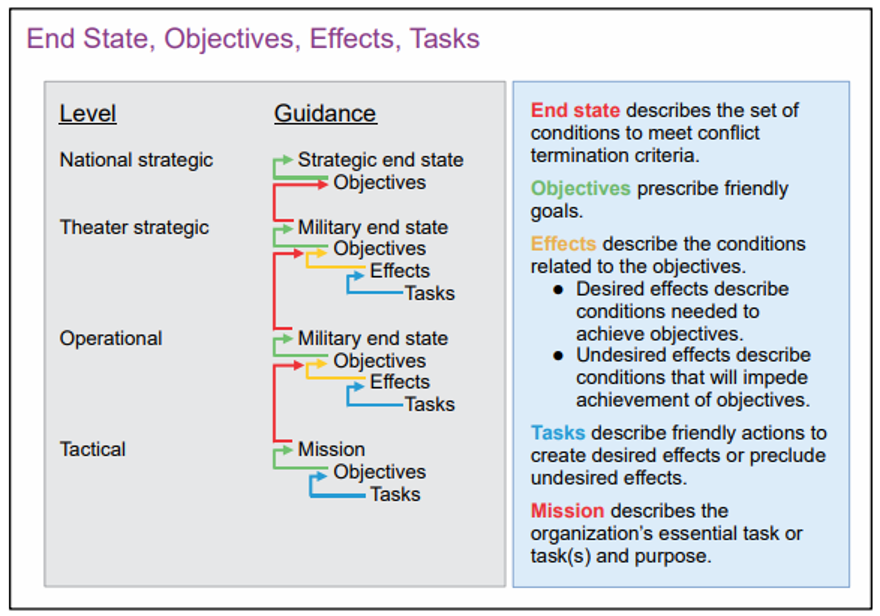

Reductionist thinking is a mental model that simplifies problems into discrete, linear cause-and-effect relationships. It assumes predictability and determinism, making it well-suited for technical problem-solving and the development of tactical or operational plans where inputs and outcomes can be tightly controlled. In the military context, reductionist approaches are valuable for designing and executing tasks such as logistics scheduling, targeting plans, or force movements. To get a sense of the linear structure, Figure 5.1 shows the typical structure of how a military plan is organized. In theory, most planners assume that this structure provides a sound structure to assess a military campaign. In practice, however this is much more difficult.

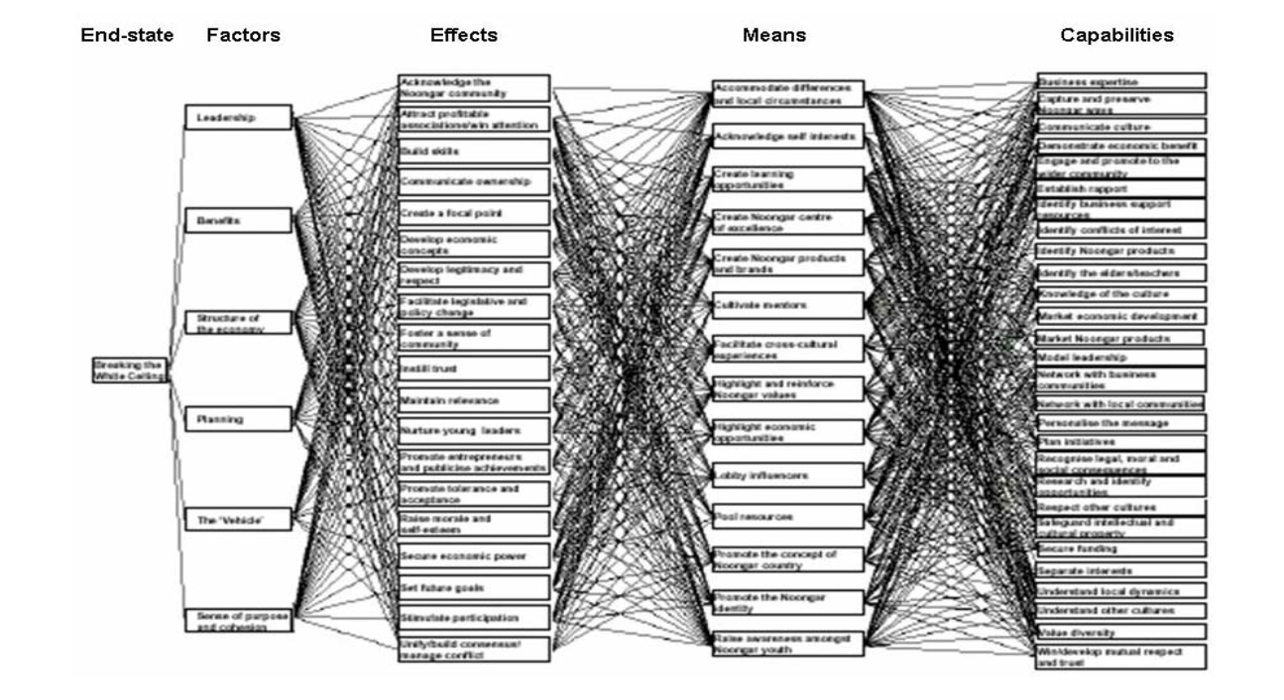

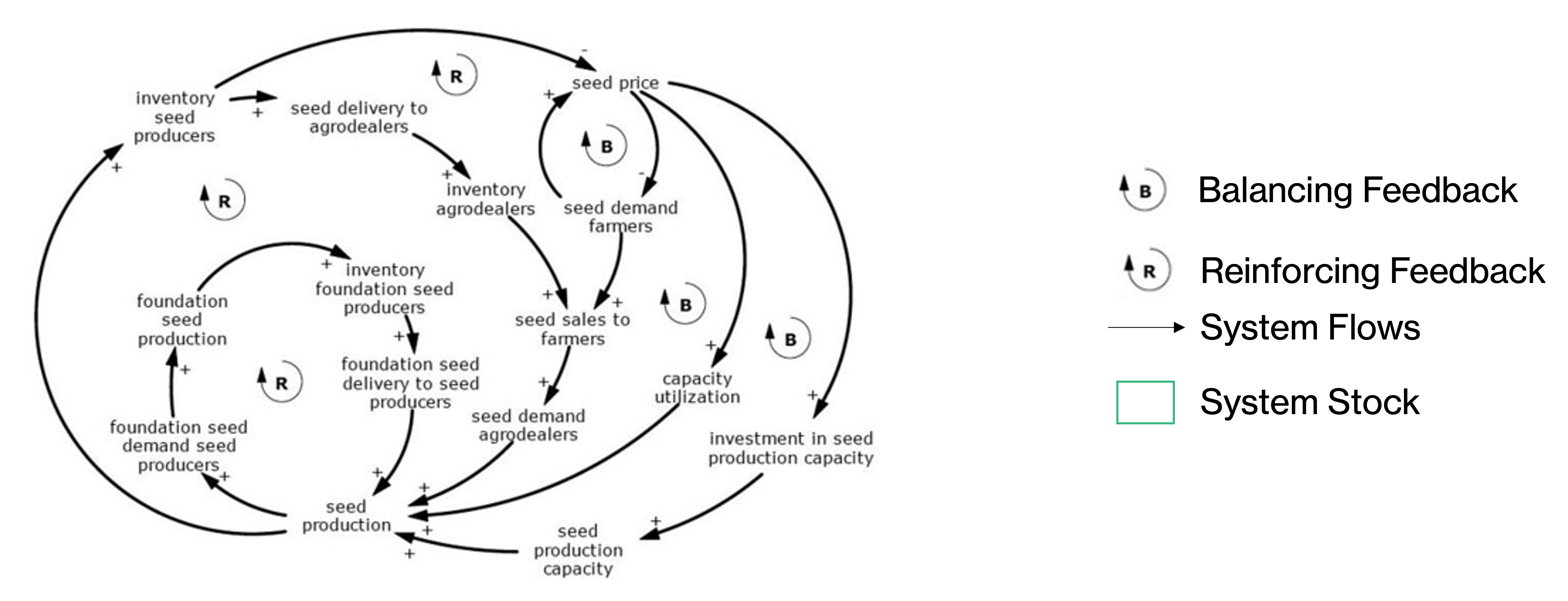

At the strategic level, the reductionist model falls short because it often ignores the complexity of interconnected systems like the one shown in Figure 5.2. Strategic effects involve numerous interdependent variables—political, cultural, economic, and informational—that interact in unpredictable ways. Applying purely reductionist thinking to such problems risks oversimplification and flawed assumptions.

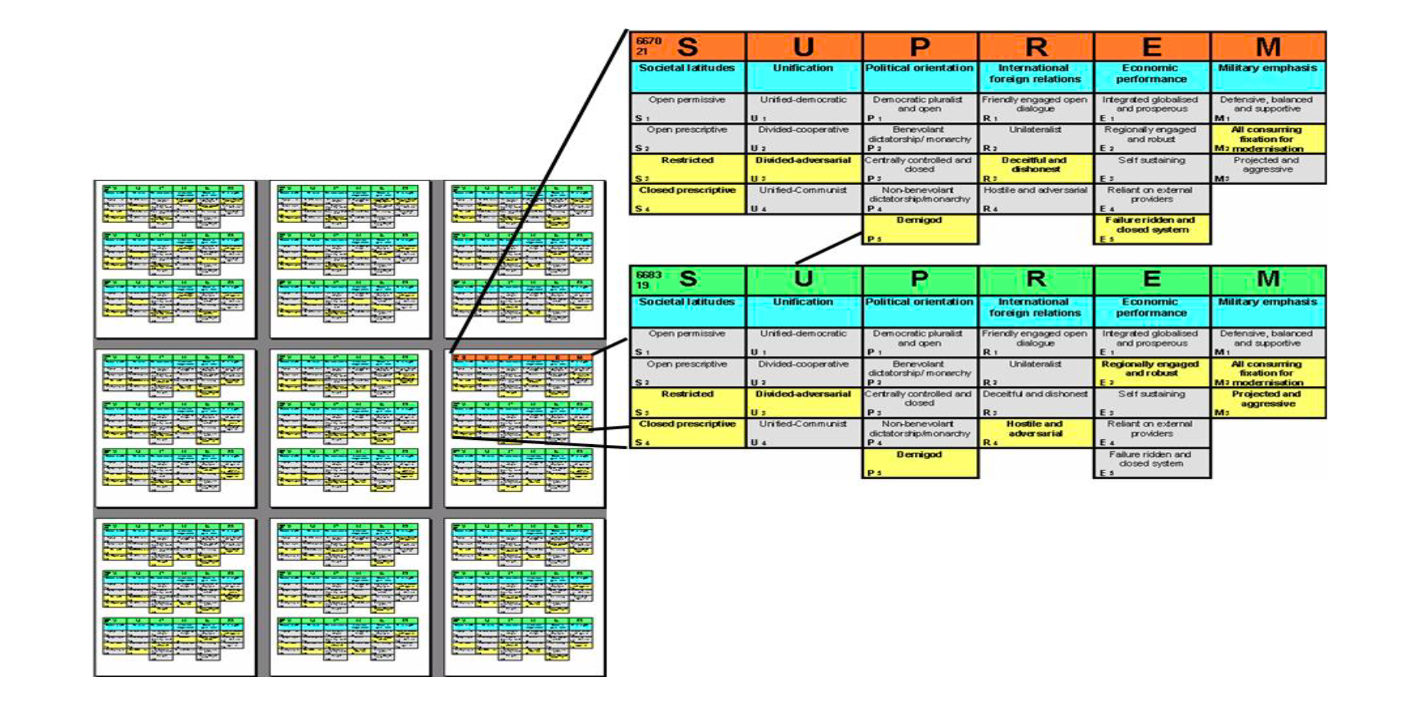

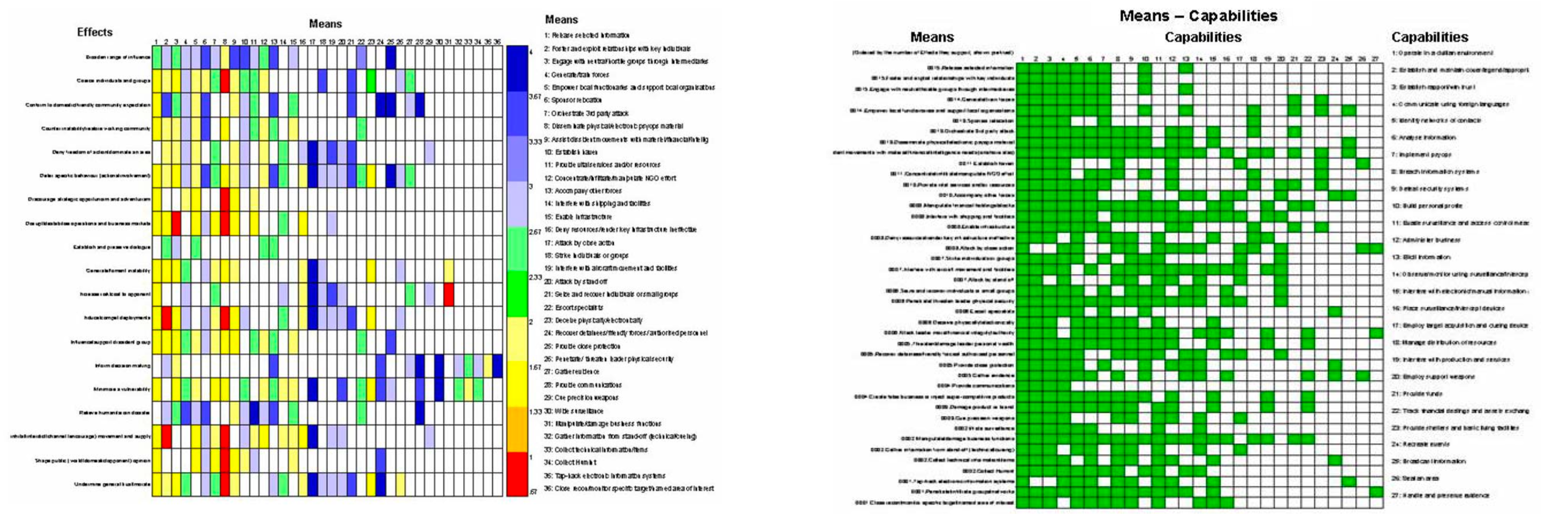

Strategic planning therefore benefits from additional tools, such as the factor–conditions matrix (Duczynski 2005) shown in Figure 5.3, which maps relationships between effects, means, and capabilities, and design/solution space analysis (Duczynski 2005) shown in Figure 5.4, which enables planners to explore multiple pathways and potential outcomes within a complex ecosystem.

5.5.2 Systems Thinking

Systems thinking offers a holistic approach to understanding and managing complexity by focusing on relationships, patterns, and interdependencies rather than isolating parts of a system like the image shown in Figure 5.5. In military strategy, it recognizes that actions in one area can trigger cascading effects in others, often in nonlinear and unexpected ways. This approach is especially suited to analyzing strategic military effects, where multiple actors, domains, and variables interact dynamically over time. Systems thinking encourages planners to account for feedback loops, time delays, and adaptive behavior—factors often overlooked in reductionist models. By viewing the operational environment as an interconnected whole, systems thinking enables a deeper appreciation of how military actions interact with political, economic, social, and informational systems. This perspective helps prevent tunnel vision, encourages creative solutions, and improves adaptability. Ultimately, systems thinking supports decision-makers in crafting strategies that are resilient, flexible, and responsive to the evolving realities of complex conflict environments.

5.6 Practical Exercise

5.6.1 Escalation Risk

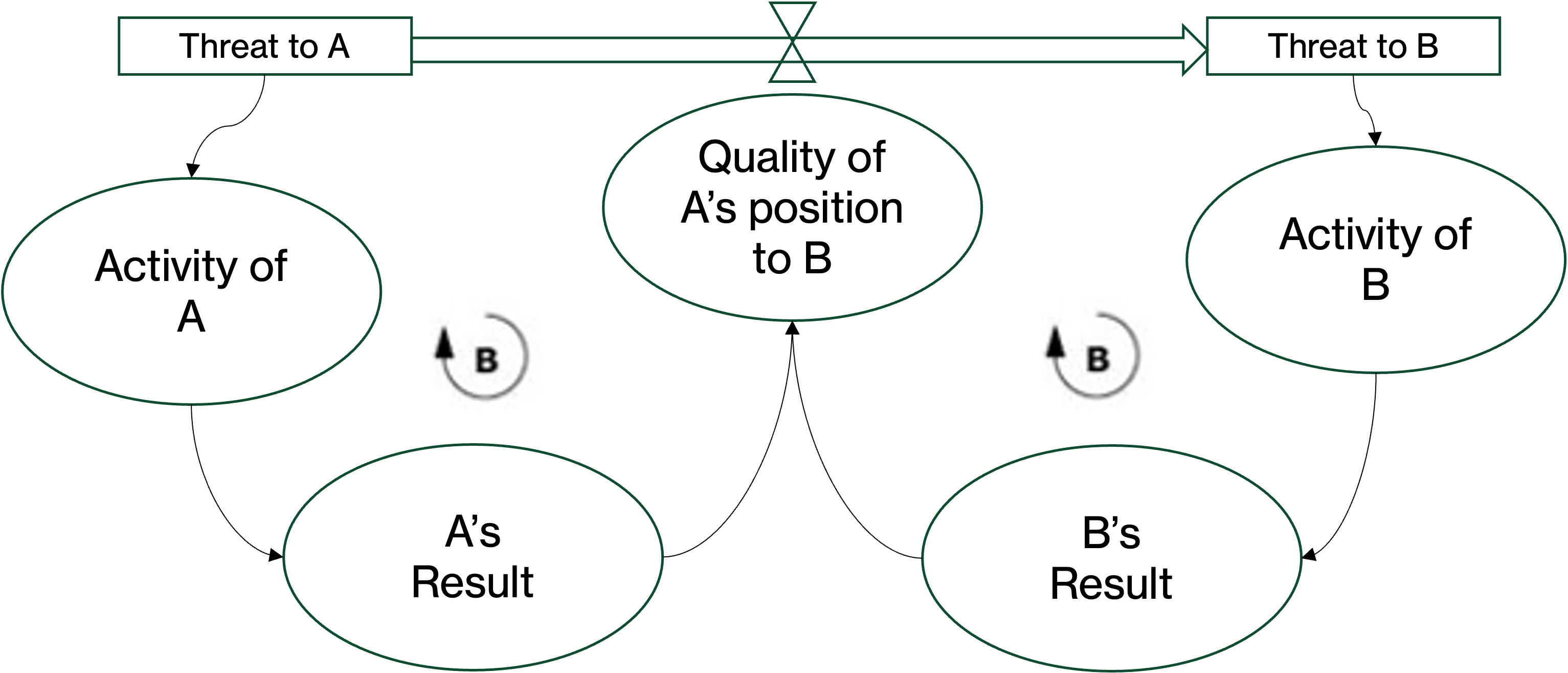

Strategic military effects become clearer when viewed through real-world examples. The Escalation Risk example illustrates how interactions between two actors’ activities, perceived threats, and resulting actions can create feedback loops that either intensify or de-escalate tensions. Strategic understanding here requires assessing not just immediate outcomes but the cumulative effects of reciprocal actions over time.

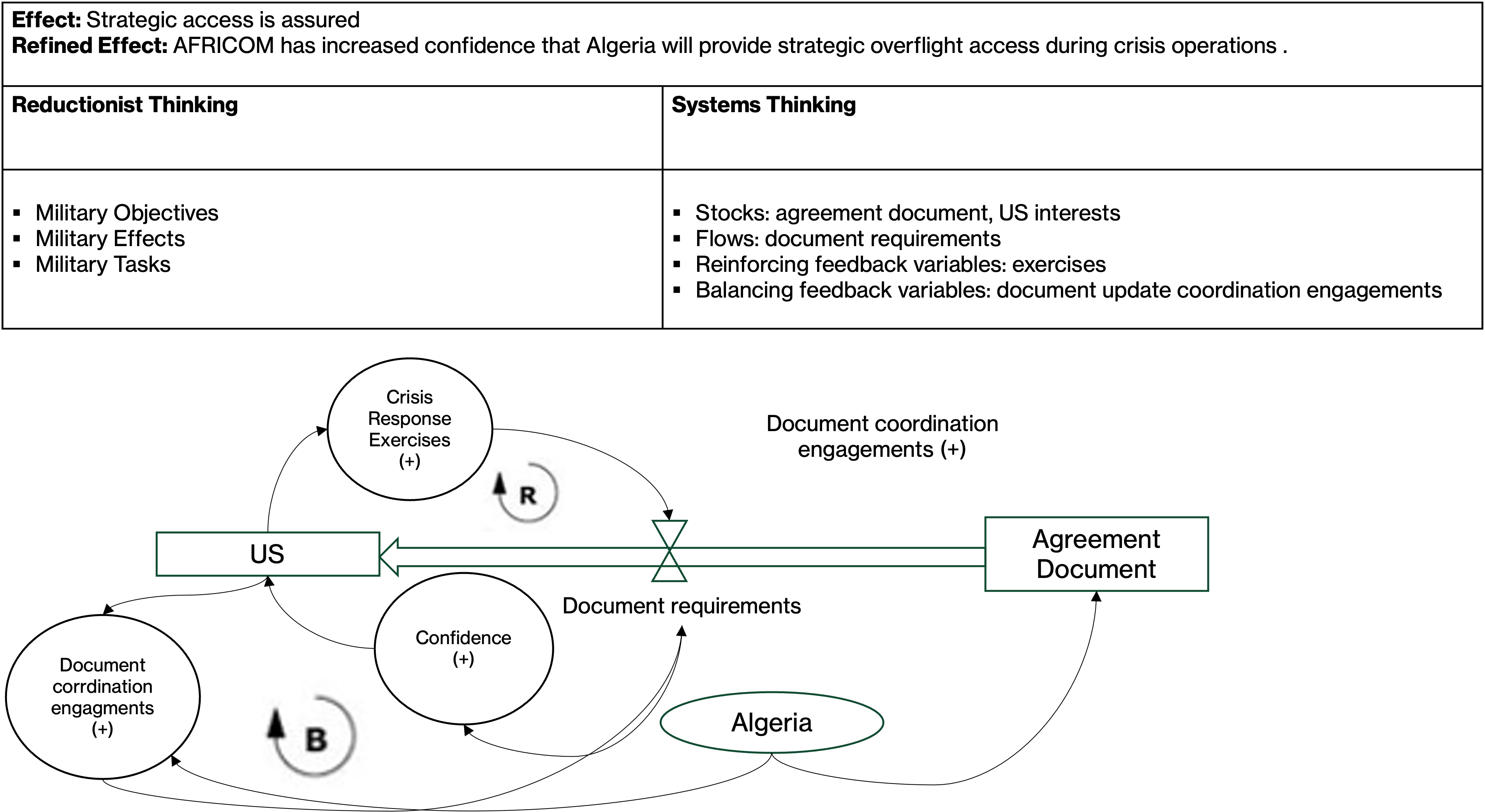

5.6.2 Overflight Agreement

The US–Algeria Agreement example shows how cooperative measures—such as document coordination and joint crisis response exercises—can build trust and confidence between nations. While the immediate operational effects may include improved interoperability or procedural alignment, the strategic effects could extend to stronger diplomatic ties and increased regional stability.

These cases demonstrate that strategic effects are rarely the result of single, isolated actions. Instead, they emerge from patterns of interaction, shaped by perceptions, intentions, and broader context. By analyzing such examples, planners can better design actions that achieve desired long-term outcomes while managing risk.